Though the fort was completed in 1847, Fort Pulaski was under the control of only two caretakers until the year 1860 when South Carolina seceded from the United States and set in motion the Civil War to shortly begin. It was at this time that Georgia’s then current governor Joseph E. Brown ordered Fort Pulaski to be taken by the state of Georgia. A steamship carrying 110 men from Savannah, Georgia traveled downriver to the fort. The fort was signed over and now belonged to the state of Georgia.

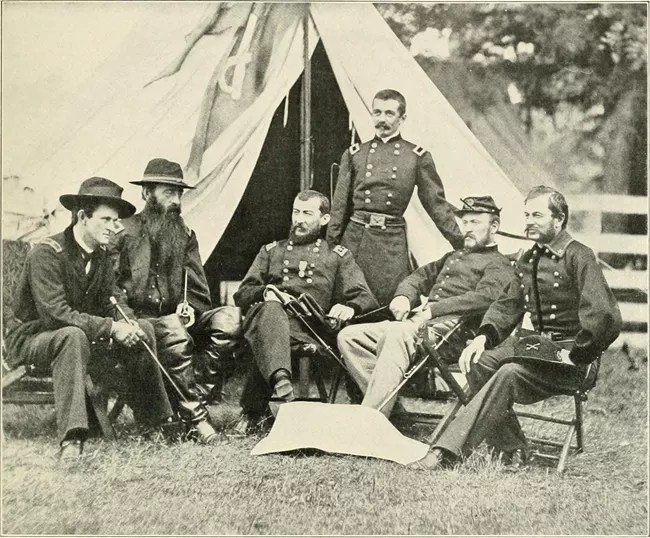

Photo by the National Archives

Following the secession of the state of Georgia in February 1861, Georgia joined the Confederate States of America. Confederate troops then moved into the fort and prepared for a possible attack that could occur any day now.

United State Forces Take Tybee Island

Tybee Island was thought as this time to be too isolated and unprepared for any conflict. By December 1861, the island had been abandoned by Confederate forces. This allowed the United States troops to gain great access across the Savannah River from Fort Pulaski. United State forces shortly began construction of batteries across the beaches of Tybee Island.

Once on Tybee Island, U.S. General Thomas Sherman thought that it might be best to by-pass Fort Pulaski and to make a direct attack on the city of Savannah. He tried to sell this plan to the commander of the U.S. Naval Forces, Rear Admiral Samuel Francis Du Pont. General Sherman would have to depend on the Navy for the transport, protection, and assistance in the siege operations he had planned. Admiral Du Pont ordered surveying of the winding waterways that led into the Savannah River above Fort Pulaski. However, when he discovered how shallow the waterways were at certain stages of the tide, he said that the whole scheme was impractical and dangerous. This difference of opinion between the U.S. Army and Navy commanders on the content of the campaign finally led to the removal of General Sherman. Meanwhile, General Sherman ordered a tight noose of batteries and gunboats to be placed around Fort Pulaski.

The Confederate supply ship, Ida, floated down the Savannah River on the morning of February 13 on one of her regular trips to Fort Pulaski. The ship was shortly met by a battery of heavy guns, which the United States had secretly constructed at Venus Point on the north bank of the Savannah River. Ida survived her encounter with the United States artillery, but it would be her last trip to the fort.

The following week, the United States completed a blockade of Fort Pulaski. They built another strong battery on the south bank of the Savannah River opposite to Venus Point. To seal the waterway, the United States entrenched two companies of infantry along Tybee Creek’s bank and assigned a gunboat to patrol the waters channel. While at the same time, they destroyed the telegraph line between the city of Savannah and Cockspur Island. From this moment on supplies nor reinforcements could be brought to the fort. The Confederate garrison would no longer be able to escape to the mainland. After February 15, the only way of communication with Savannah was by a courier who came and went by night through the marshes.

Five companies formed the garrison of Fort Pulaski as a whole when the fort was cut off. Company B of the Oglethorpe Light Infantry, the Washington Volunteers, the German Volunteers, and the Montgomery Guards were members of the 1st Regiment of Georgia Volunteers. The total strength of the garrison was created by 385 officers and men. In command was Charles H. Olmstead, who had been elected as colonel of the 1st Volunteer Regiment on December 26. There were 48 guns to defend the fort from any outside danger.

The armament was placed throughout the fort evenly to command all approaches. On the ramparts facing Tybee Island there were five 8-inch and four 10-inch columbiads, one 24-pounder Blakely rifle, and two 10-inch seacoast mortars. In the casemates bearing on Tybee Island were one 8-inch columbiad and four 32-pounder guns. The batteries outside of Fort Pulaski were two 12-inch and one 10-inch seacoast mortars. The remaining guns were mounted and faced to command the North Channel of the Savannah River and the marshes to the west. The Confederates had officially prepared Fort Pulaski for battle.

The Battle of Fort Pulaski

On the morning of April 10, 1862, United States forces asked for the Confederate army to surrender Fort Pulaski to prevent needless loss of life. Colonel Charles H. Olmstead, the current commander of the Confederate garrison, rejected the offer. The men inside of Fort Pulaski learned that they had little to fear from the United States mortars.

Early on in the battle 10-inch and 13-inch mortar shells exploded high through out the air and fell outside the fort. The few mortar shells that dropped on the parade buried themselves in the ground. Those that did explode threw up harmless geysers of mud. The fort quivered and shook when a solid shot from a columbiad hit a wall. About 2 hours after the battle began, one of the shots entered an embrasure and dismounted the casemate gun. Several soldiers of the gun crew were wounded, one man was wounded so severely that it was necessary to amputate his arm immediately.

At noon onlookers on Tybee Island counted 47 scars on the southeast corner of Fort Pulaski. It was obvious that several of the embrasures had been considerably enlarged. During the afternoon the fire had slackened on both sides. After sunset not more than 7 or 8 shells per hour were thrown until the daylight of the next morning approached.

At the end of the day to onlookers on Tybee Island, Fort Pulaski even with its dents and scars, looked as solid and capable of resistance as what it did before. There was a common feeling throughout the US soldiers that the day’s work had not greatly hastened the surrender. The mortars had proved to be a disappointment, and the effect of the breaching fire could not be determined. Although there had been many close calls, no one had been hurt in the US batteries.

Had Gillmore been able to inspect Fort Pulaski at the end of the first day, he would have had reason to be happy. The place was in shambles. Mostly all of the barbette guns and mortars bearing towards Tybee Island had been dismounted and only two of the five casemate guns were still in order. At the southeast angle of the fort, the whole wall from the top to the moat was flaked away to a depth of from 2 to 4 feet. United States bombardment opened two very large holes in the walls of the fort.

Surrender

At daylight of Friday morning, the troops reopened fire with fresh energy on both sides. From Tybee Island, Gillmore’s gunners began resuming the work of breaching with determination. The effect was almost apparent as soon as it happened in the enlargement of the two embrasures on the left of the southeast face of Fort Pulaski. The fort’s fire was far less on target than that of the United States guns. The batteries on Tybee Island were almost all masked behind a low sand ridge and were protected by heavy sandbag revetments. Most of the Confederate shots and shells buried themselves in the sand or traveled completely over the United States batteries and trenches. At about 9 o’clock, the troops received their only casualty. A solid shot from Fort Pulaski entered a gun embrasure in Battery McClellan striking a private soldier. He was wounded so severely that he died soon after.

During the morning, the United States Naval gunboat, Norwich, began to fire shots against the northeast face of the fort. The range was too great, and the ships shots struck only glancing blows on the fort’s brick walls. A battery on Long Island opened up at long range of shots from the west. Shots were landing on the south wall from guns located on a barge in Tybee Creek.

At noon, most of the United States fire was directed towards the guns on the ramparts of the fort. Within half an hour these guns were quiet. During this time two large holes had been opened through the walls and the inside of the fort was visible from Tybee Island. The interior arches of the fort had been laid bare, and a barbette gun on the parapet was tottering, ready to fall. It was for certain that the whole east angle would soon be in ruins. U.S. General Benham gave orders to prepare to take Fort Pulaski by direct assault.

At Fort Pulaski, when the men were ordered from the ramparts to allow the guns to cool down, Pvt. L. W. Landershine thought that “things looked blue.” One man had been mortally wounded, another man had his foot taken off by the recoil of a gun, and a dozen others had been struck by fragments of shells. Projectiles from the rifle batteries were passing completely through the breach and sweeping across the parade, striking against the walls of the north magazine in which 40,000 pounds of black powder was stored inside of.

The moment had come for Olmstead to make a decision. There were only two options open. He could fight on against the overwhelming odds, or he could admit the army’s defeat. A difficult choice for the 25-year-old colonel to make. Impressed by the utter hopelessness of the current situation and believing the lives inside of the garrison had to be his next care, he gave the order for surrender.

Private Landershine, who was discussing at this time the state of affairs with his comrades, stated, “About 2-1/2 p. m. I seen Col. Olmstead and Capt. Sims go past with a rammer and a sheet, we all knew that it was over with us and we would have to give up.”

The Confederate flag was then lowered half way and a final gun was fired from a casemate. Then the flag was hauled down and the white sheet took its place. An old era in coastal fortifications had come to an end.

On Tybee there was major rejoicing. Men danced together on the beach, shook hands, and cheered General Gillmore as he rode along the line. At King’s Landing, Gillmore entered on a small boat with his aides. The passage up the South Channel was rough, the skiff ran aground and was nearly swamped by the heavy seas. Soaked with the salt tides of the Savannah River, the party landed at Cockspur Island and advanced toward the fort under a flag of truce. Colonel Olmstead was waiting at the entrance of the fort. He showed the general the way to his quarters, and, during an hour alone with General Gillmore, the terms of the surrender were settled. After inspecting the fort, the general took leave.

In Colonel Olmstead’s quarters lighted by the half-light of candles, the officers of the fort gave up their swords to General Hunter’s representative, Maj. Charles G. Halpine. The weapons were laid on a table, and each officer, according to his rank, advanced in turn, mentioned his name and title, and spoke a few words appropriate to the occasion. Colonel Olmstead remarked when it became his turn to speak, “I yield my sword, but I trust I have not disgraced it.”

The men of the garrison were separated by companies on the parade, stacked their arms, and marched to quarters for the night. The United States Flag was then raised over the ramparts, and Pulaski again became part of the possessions, as well as the property, of the United States. However, the terms of the surrender were unconditional. Col. Olmstead along with his officers delivered their swords to Major Halpine after the surrender of Fort Pulaski.

Charles Hart Olmstead was born in Savannah, Georgia and attended the Georgia Military Institute. In 1861, Mr. Olmstead was given command of the Confederate garrison inside Fort Pulaski. On April 11, 1862, he wrote to his beloved wife:

“My dear wife,

I address you under circumstances of the most painful nature. Fort Pulaski has fallen and the whole garrison are prisoners.

…It soon became evident to my mind that if the enemy continued to fire as they had begun the walls must yield. Shot after shot hit immediately about our embrasures…

Officers and men behaved most gallantly, everyone was cool and collected…The men when ordered on the parapet, went immediately with the most cheerful alacrity, though the missiles of death were flying about at the most fearful rate. Thirteen- inch mortar shells, Columbiad shells, Parrott shells, rifle shots were shrieking through the air in every direction, while the ear was deafened by the tremendous explosions that followed each other without cessation…

On taking a survey of the Fort after the firing had ceased, my worst fears were confirmed, the Angle immediately opposed to the fire of the enemy was terribly shattered and I was convinced that another day would breach it entirely.

…I found that the breach in our wall had become so alarmingly large that shots from the batteries of the enemy were passing clear through and striking directly on the brickwork of the magazine. It was simply a question of a few hours as to whether we should yield or be blown into perdition by our own powder…

I gave the necessary orders for a Surrender. Oh, my dear wife, how can I describe to you the bitterness of that moment. It seemed as if my heart would break. I cannot write now all the details of our surrender; it pains me too much to think of them now…”

Corporal Howard served in Company F of the 48th New York Infantry. The infantry witnessed the bombardment from nearby Daufuskie Island. Howard kept a diary during his time that he spent in the 48th. This period of time spanned from his enlistment in September 1861 to just prior to his wounding at the failed Union assault on Fort Wagner in July 1863.

“April 10th, 1862

Bombardment of Fort Pulaski. Commenced at 8 O Clock precisely…Soon as I got relieved went up to the Genl’s quarters as fast as possible and secured a fire view, and while sitting there the long roll beat to quarters, ran back to secure my arms & ammunition and fell in line. After the regiment was formed, we stacked arms and was dismissed with permission to watch the bombardment…the whole shore of Tybee had opened upon the Fort. Firing continued all day and night – without any pausing whatever.

April 11th 1862

No cessation of firing this morning. Fire is more rapid than yesterday. At long intervals the Fort replies but they appear to be giving in. 2 and 30 P.M…the rebel flag came down the Fort has surrenderd. The bombardment lasted 36 hours.

April 12th 1862

This morning the Stars & stripes are waving from the ramparts of Pulaski. The fleet runs up the river to the Fort.

April 13th 1862

Col. Perry and Dr. Mulford goes to the Fort various rumors circulating in Camp that we are to garrison the Fort. A great deal of grumbling at the receipt of this news.”

Mr. Wilson served as a topographical engineer for the United States forces who were stationed on Tybee Island. Just prior to the bombardment, James delivered the Union army’s message that demanded the Confederates to surrender at the Confederate garrison inside of Fort Pulaski. On April 30, 1862, he wrote fellow Union general James McPherson:

“My dear McPherson

…Your letter of the 8th ult, found us engaged in the very heavy work of preparing for the reduction of Pulaski, it was tedious very laborious and above all experimental. Gen’l Gillmore and the young men had to contend with the fears, doubts, adverse opinions and remonstrances of old fogies as well as natural obstacles of no insignificant character…In face of all this Gillmore hung out, carried out his plans and attacked the fort, with what success you know.

At the distance of 1700 yards, in about 17 hours firing two breaches entirely practicable were effected and two others opened. In two days more we would have battered down the entire face exposed to our direct fire…The whole affair is replete with instinctive results. The most important of which, I consider to be that the ordinary thickness of brick escarpments is not sufficient to resist breaching operations at anything less than 2500 yards with a judiciously selected batteries of heavy rifles and 10 in guns I have no hesitation in saying that a breach can be effected at this distance quite as easily as at 300 yards with the old fashioned arm. Notwithstanding all this, so far as concerns the danger of siege operations, the old fashioned works will answer admirably the primary purpose of delaying the enemy. Pulaski has kept us out of Savannah for four months, and we are not there yet and probably will not be soon…”